When Learning Trumps Perfection

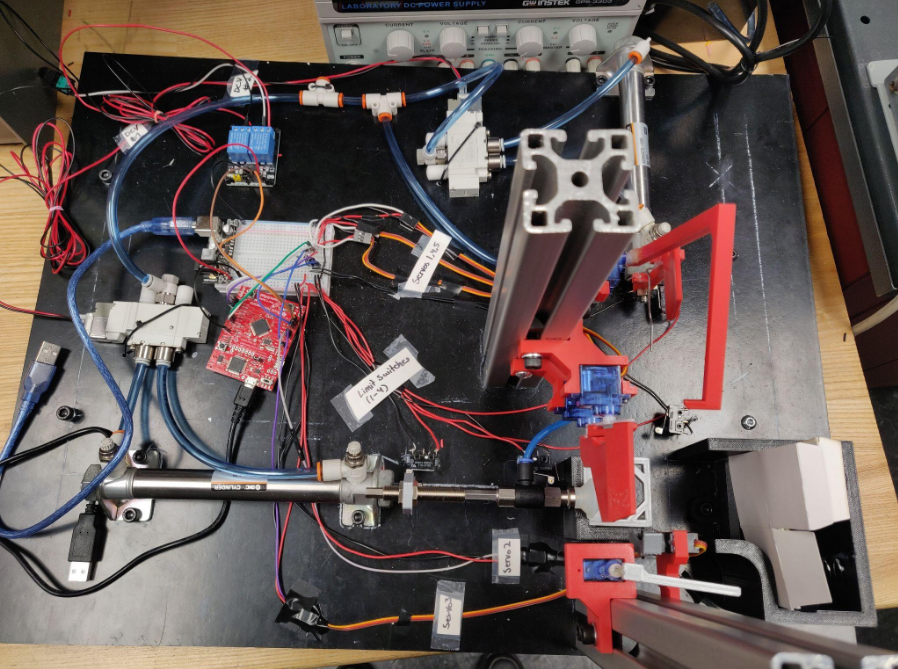

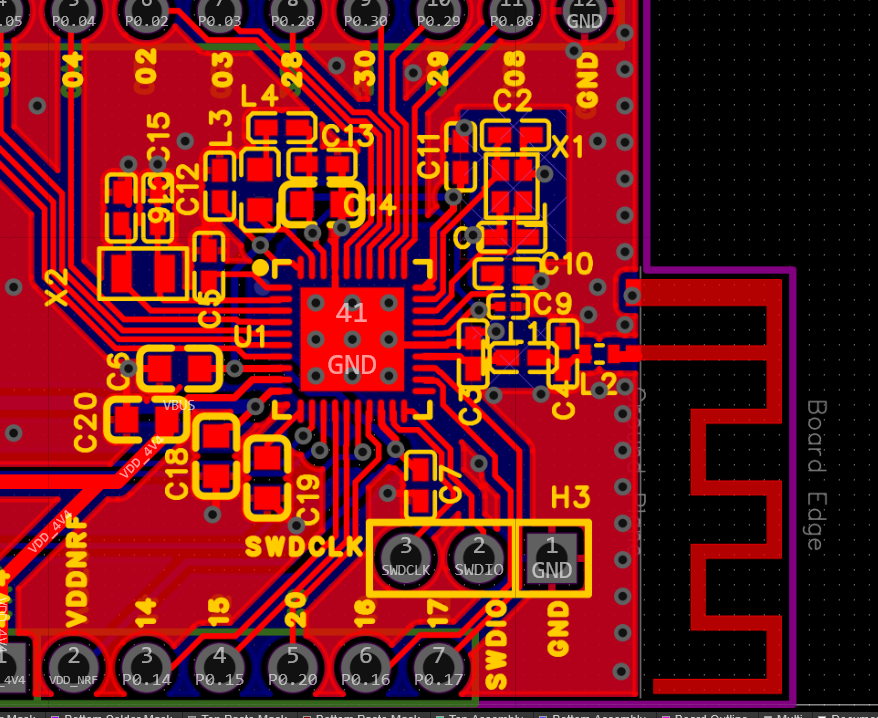

I’ve been diving into embedded driver development recently, specifically writing an SPI driver for STM32 microcontrollers. I’ve been following a course (MCU1 from FastBit Academy) for embedded driver development. The GPIO section was pretty structured, and by the time I got to SPI, I felt ready to take a bit more control and design my own API.

Initially, things went smoothly. I got a basic blocking transmission working first. It felt good to make something from scratch that actually did what it was supposed to. From there, I implemented interrupt-driven transmission, even tying it to a button press. Seeing my interrupt-based code run successfully was pretty exciting.

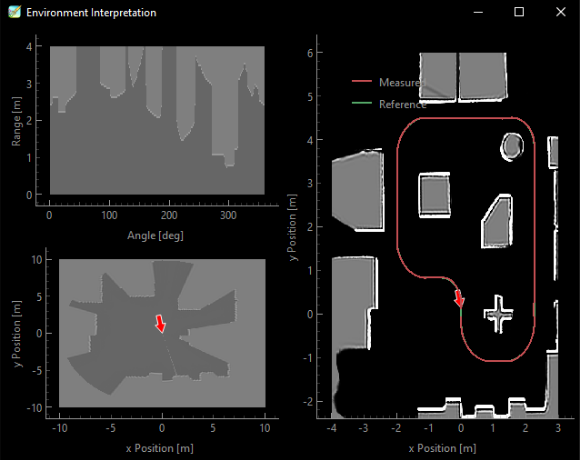

Feeling confident, I moved on to communicating with an Arduino using full-duplex SPI. The course used polling, but since interrupts had worked out well before, I decided to stick with them. But here I ran into trouble. As soon as I started juggling transmission and reception simultaneously, managing timing requirements, and handling edge cases, things got complicated.

I had fallen into the trap of trying to do too much too soon. Instead of implementing just the parts I needed to learn more about the peripheral, I jumped the gun trying to account for every future scenario. (We’ve all been there right?). Ultimately I decided to look through the official STM32 HAL library, hoping to study what professional implementations look like and try to model my API after it.

Looking at ST’s HAL was overwhelming at first. It’s comprehensive and extremely generalized, covering every possible configuration. A part of me wanted to match that level of abstraction even when I barely knew how half the features worked. The scope-creep gods had definitely found another victim.

I finally realized that instead of solving problems I was inventing them. I didn’t need 90% of the flexibility I was designing for. The purpose of my SPI driver was to learn, not to be perfectly abstract and reusable.

This realization brought me back down to earth and it reminded me of these two important concepts:

- YAGNI (You Ain’t Gonna Need It): Don’t build features you don’t actually need yet.

- KISS (Keep It Simple, Stupid): Build the simplest version that works for your current problem. No extra layers, no unnecessary abstractions.

I recently saw a comment from another embedded dev on reddit that summed this up perfectly:

“One suggestion, don’t try to create a generic abstraction layer for a peripheral or functionality the first time you use something. You’ll almost certainly end up making incorrect assumptions about how you will use it that means when you attempt to re-use the code you end up fighting against the abstraction model. Once you’ve used something a few times you’ll have a far better idea of what works and what doesn’t and can then structure the generic code in a way that works well.”

See the original comment here

I stepped back and decided to allow the SPI driver to handle only what was necessary at that moment so that I could move on and learn the next thing. It wasn’t comprehensive but it was straightforward, functional, and easy to debug. Importantly, I could actually understand what each part was doing, and next time I can design a better architecture using what I’ve learned.

Through this experience, I’ve learned something valuable about software development. Clean code, abstraction, and reusability are important, but only if they actually help you solve your real problems. Creating a plan with intention, sticking to it, and keeping focus on what’s actually needed helps projects move forward efficiently and reduces unnecessary complexity.

This experience also highlighted some gaps in my understanding of software architecture, state management, and general best practices. To address that, I’ve recently started reading Making Embedded Systems: Design Patterns for Great Software by Elecia White. I’ll be sharing what I learn as I go through it, hoping to fill in those gaps and become a better embedded developer.

I’ll probably rewrite this driver again, and again, but each iteration will be guided by the lessons of the previous one, and the actual requirements of the problem in front of me.